Quantile-based categorical statistics

Johannes Jenkner, Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH Zurich, Switzerland

Traditional point-to-point verification is more and more

superseded by situation-based verification such as an object-oriented mode. One

main reason is that difficulties are encountered while interpreting the outcome

of a conventional contingency table based on amplitude thresholds. Firstly, a

predetermined amplitude threshold splits the distributions under comparison at

an unknown location. In an extreme case, single entries of the contingency

table can become zero. Then some scores cannot be computed (due to a division

by zero) and statements about model behavior are hard to make. Secondly, the

distributions under comparison usually differ considerably with respect to

their range of values. Customary scores do not fulfill the requirements for

equitability (Gandin and Murphy, 1992) and fail to be firm with respect to

hedging (Stephenson, 2000). Thirdly, the joint distribution usually comprises

multiple degrees of freedom. In the case of a 2x2 amplitude-based contingency

table, three linearly independent scores are needed to display all verification

aspects (Stephenson, 2000). It is possible to draw complementary information

from the considered datasets, if concurrent scores are applied simultaneously.

But it remains unclear, how to attribute individual verification aspects to

measures which are not totally independent from each other. Fourthly, it is not

meaningful to integrate amplitude-based scores over a range of intensities.

Averages over multiple thresholds are difficult to interpret, because it is not

obvious how many data points fall within individual ranges of thresholds.

To counteract the addressed drawbacks of categorical

statistics, frequency thresholds, i.e. quantiles, can be used instead of

amplitude thresholds to define the contingency table. Then two additional

interrelations are automatically included into the conceptual formulation:

false alarms = misses

misses + correct negatives = pN

Note that p denotes the quantile probability (0 < p

< 1) and N stands for the sample size. Due to the first equation, the

contingency table benefits from a calibration and is not influenced by the bias

any more. The problem of hedging is eluded, because it is no longer possible to

change the number of forecasted events without adjusting the number of observed

events. Due to the second equation, the base rate (1–p) is fixed a priori

and determines the rarity of events. The single remaining degree of freedom uniquely

describes the joint distribution. Thus, it is now possible to describe the

forecast accuracy or the skill related to individual intensities by means of a

single score.

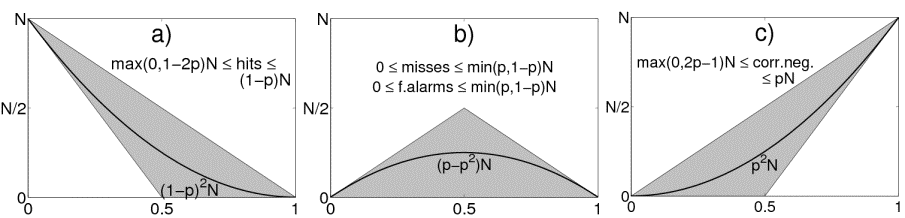

Depending on the quantile probability, the four

entries of the contingency table only vary within a limited span (Fig. 1). If

the quantile probability is below 0.5, there are always some hits by definition.

If the quantile probability is above 0.5, there are always some correct

negatives by definition. The misses and false alarms are consistently limited

at the top. They are restricted either by the number of non-events (p < 0.5)

or by the number of events (p > 0.5). A random forecast imposes strongly

varying frequencies for all entries in the contingency table. A score is preferably

independent from all variations caused by the base rate.

Figure 1: Possible entries (gray shaded) and random

expectation values (thick black lines) of the four entries in the 2x2

contingency table: a) hits, b) misses or false alarms, c) correct negatives.

The x-axis displays the range of quantile probabilities and the y-axis shows

the number of data points.

The Peirce Skill Score (PSS, equivalent to the True

Skill Statistics and the Hanssen-Kuipers Discriminant) is able to measure skill

without being perturbed by the base rate (e.g. Woodcock, 1976, Mason, 1989).

Thus, the PSS is ideally suited to measure the joint distribution, i.e. to

display the forecast accuracy on its own. Owing to the definition of a

quantile, the computation of the PSS simplifies to:

PSS = 1 – misses/missesrand

missesrand = (p – p2)N

To complement the verification, the bias is represented by the absolute (abs)

or relative (rel) quantile difference (QD):

QDabs = qmod – qobs

QDrel

= 2QDabs/(qobs + qmod)

Note that qobs and qmod denote

the observed and modeled (forecasted) quantile values, respectively. QDrel

is computed according to the amplitude component in the SAL measure (Wernli

et.al., 2008). The value therefore varies between -2 and

+2. The QD and the debiased PSS split the total error

into the independent components of bias and accuracy. Together, they provide a

complete verification set with the ability to assess the whole range of

intensities along the distributions under comparison.

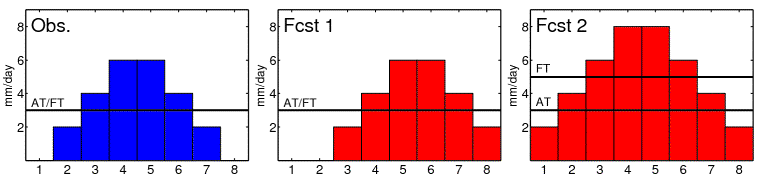

The conventional PSS (with amplitude thresholds)

cannot distinguish between an amplitude error and a shift error. Only the

quantile-based contingency table provides the opportunity to distinguish

between the two types of errors. The new concept can be exemplified by means of

a simple forecast paradigm. Consider a constructed forecast problem with daily

rainfall amounts for 8 days (Fig. 2). The observed distribution (Obs.) is

symmetric and peaks on day 4 and 5. A first forecaster (Fcst 1) is able to

estimate the right amounts, but predicts the rainfall one day too late, meaning

that his forecast exhibits a shift error. A second forecaster (Fcst 2) is able

to estimate the right timing, but overpredicts the rainfall by 2 mm/day,

meaning that his forecast exhibits a bias. We want to compare both forecasts by

means of the PSS now. The conventional PSS is applied with an amplitude

threshold (AT) of 3 mm/day. The result is an equal scoring of PSS = 0.5 for

both forecasters. Thus, both forecasts show the same performance, but we cannot

assess the error type. The debiased PSS is applied with a frequency threshold

(FT) of 50%. The result is still PSS = 0.5 for the first forecaster, but it is

raised to PSS = 1 for the second forecaster. Since the bias is disregarded in

the PSS now, the second forecast is rated optimal. To account for the amplitude

error, the quantile difference is evaluated. It constitutes QDabs =

0 mm, i.e. QDrel = 0, for the first forecast. Likewise, it

constitutes QDabs = 2 mm, i.e. QDrel = 0.5, for the

second forecast. It is now possible to clearly distinguish between a shift

error and a bias. Thus, room for additional insights is provided.

Figure 2: Forecast paradigm of forecasting rainfall amounts

for 8 days: Observations (left), first forecast (middle), second forecast

(right). The first forecast exhibits a pure shift error of 1 day. The second

forecast exhibits a pure bias with an overestimation of 2 mm/day. The selected amplitude threshold (AT)

constitutes 3 mm/day. The selected frequency threshold (FT) corresponds to the

50% quantile.

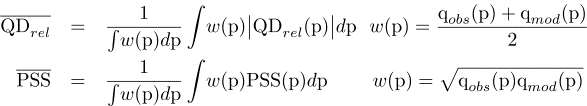

To

aggregate the scores over intensities, weighted averages can be computed over

quantiles. Thereby, QDrel is integrated with its absolute value,

because individual quantiles with an over- and underestimation can cancel each

other out otherwise. The weights w(p) correspond to the arithmetic and the

geometric mean for the QDrel and the PSS, respectively:

A convenient advantage of using quantiles is a

stabilization of the sample uncertainty for rare events. Bootstrap confidence

intervals for the PSS reveal that the uncertainty usually only slightly

increases while moving towards extreme quantiles. Quantile probabilities

inherently are not affected by amplitude uncertainties, but their

transformation to quantile values, i.e. corresponding amplitudes, suffers from

ambiguities. We can achieve a high confidence for the PSS value for a certain

quantile, but still hold a low confidence for the quantile estimation. However,

since arbitrary amplitudes are not related to the sample distribution, it is

sometimes useful only to consider quantiles, corresponding for example to

return periods of extreme rainfall events.

An elaborate description of the methodology as well as

an application to daily rainfall forecasts of the COSMO1

model over Switzerland can be found in Jenkner

et.al. (2008).

A printable pdf version of this web site can be

downloaded here.

References:

Gandin, L.S., and A.H. Murphy, 1992: Equitable skill

scores for categorical forecasts. Mon. Wea. Rev., 120,

361-370

Jenkner, J., C. Frei, and C. Schwierz, 2008:

Quantile-based short-range QPF evaluation over Switzerland. Submitted to

Meteorol. Z. download

Mason, I., 1989: Dependence of the critical success

index on sample climate and threshold probability. Aust. Met. Mag., 75-81

Stephenson, D.B., 2000: Use of the Odds Ratio for

diagnosing forecast skill. Wea. Forecasting, 15, 221-232

Wernli, H., M. Paulat, M. Hagen, and C. Frei, 2008:

SAL – a novel quality measure for the verification of quantitative

precipitation forecasts. Mon. Wea. Rev., in press

Woodcock, F., 1976: Evaluation of Yes-No forecasts for

scientific and administrative purposes. Mon. Wea. Rev., 104,

1209-1214